ADVERTISEMENT

Treating and Preventing Clostridium difficile Infection in Long-Term Care Facilities

A Letter to the Editor was published about this article on March 11, 2019 noting an update to the treatment guidelines.

Abstract: The spore-forming bacteria Clostridium difficile (C diff) can cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon. C diff infection (CDI) is most common in older adults who have been hospitalized or who reside in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) and typically occurs after use of antibiotic medications. In recent years, CDIs have become more frequent, severe, and difficult to treat. An overview of CDI in older adults and in LTCFs particularly is provided below, including background, prevention, and treatment. An accompanying quick-reference Tip Sheet is also provided for ease of dissemination and education in facilities.

Key words: Clostridium difficile, diarrhea, long-term care facilities, colitis

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacteria Clostridium difficile (C diff), which produce the noninvasive toxins A and B that lead to diarrheal illness.1 Presentation of CDI can range from asymptomatic carriage to severe ileus and toxic megacolon. Most people with CDI experience watery diarrhea, often with an elevated white blood cell count.2,3 C diff spreads by way of the fecal-oral route, which is why hand hygiene and appropriate environmental cleaning are the primary means of halting the spread of disease in any setting. Active surveillance is important to initiating early effective treatment and stopping disease transmission.

CDI has several risk factors, including increasing age, comorbidities, and medication use (particularly antibiotics), in addition to other factors. Several studies have shown that living in a long-term care facility (LTCF) is an independent risk factor for CDI and that C diff is endemic in LTCFs, with colonization rates ranging from 4% to 20%.3-5 CDI in the LTCF setting occurs at rates similar to those of hospital settings and range from 0.8 to 14.1 cases per 10,000 resident days or 1.5% to 3.8% of LTCF admissions.4,6-9 It is believed that the majority of CDI cases are acquired in the acute hospital setting,10 but this is difficult to assess in epidemiologic studies and is controversial. One study of a Veterans Affairs facility in Pittsburgh, PA, found that 40% of CDI cases occurred after 30 days of admission to the LTCF, so it can be difficult to ascertain at which point the colonization occurred.11 A more recent study also suggested that colonization occurred more frequently after admission to a LTCF than in the hospital.12 CDI in this setting tends to be more severe but is significantly understudied.13,14 Clinical features of CDI in older adults do not differ from those in younger adults, and surveillance recommendations are the same for community-dwelling older adults and LTCF residents.15

This article provides an overview of CDI in older adults, including CDI screening and treatment in LTCFs with an accompanying quick-reference Tip Sheet (above reference list) for health care professionals.

Prevention

The most important way to reduce the incidence of CDI is to limit the use of antibiotic agents.16 Infection control procedures that help providers distinguish among asymptomatic bacterial carriage, viral illness, and true bacterial disease are critical for antibiotic stewardship. Mixed evidence exists for the use of probiotics,4,17 with the best evidence shown for the prevention of recurrent illness18; however, the overall risk of probiotic use is low, and it should be considered in conjunction with systemic antibiotics during acute infections to prevent CDI.19

Studies have shown that good hand hygiene (glove use and hand washing)20 and use of disposable equipment such as disposable gowns16,21 are effective in reducing the carriage and transmission of C diff. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are not recommended. When sanitizing rooms and medical equipment, providers should understand that C diff is not easily killed with routine cleaning agents because of the formation of spores, which can only be eradicated through mechanical scrubbing with soap and water, 10% bleach solution, or 1:10 hypochlorite solution.4

It should be noted that restricted-use antibiotics policy, disposable gowns, environmental cleaning and isolation techniques, and multi-intervention infection control procedures2 have all been shown to effectively reduce the incidence of CDI in hospital settings, but their efficacy still needs to be confirmed in the LTCF setting. The routine use of probiotics for the primary and secondary prevention of CDI and the safety/efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) also need further study in LTCFs.22

Diagnostic Testing

Testing for C diff should take place when a person with risk factors for CDI (Table 1) experiences more than 3 unformed stools in a 24-hour period with no other explanation for the diarrhea.16 A liquid stool sample should be obtained to test for the presence of C diff toxin and bacteria. The newer polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are recommended,1 but recent evidence suggests that toxin immunoassay tests are important to confirm clinical disease and to adequately stratify the patient’s risk.23,24 The use of PCR molecular testing alone may lead to the misclassification of carrier status as active disease and to unnecessary overtreatment. LTCF clinicians and medical directors should be aware of local laboratory testing procedures and create diagnostic protocols based on available tests. If the diagnosis is still unclear, colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy showing pseudomembranes is pathognomonic for CDI but is rarely performed. It is not recommended to test asymptomatic patients or to check for cure following a treatment course.1 Attempts to eradicate asymptomatic carriers have not led to reduced clinical disease in carriers or close contacts.3,16,25

Once CDI has been identified, isolation techniques can help to reduce the spread of disease3; however, strict isolation is difficult in a LTCF, since it serves as a person’s residence. Experts recommend that a person with CDI remain in his or her room until the diarrhea has resolved.16 If it is not possible to offer a private room for people with CDI, it is recommended to cohort people with CDI.

Treatment

Treatment should be initiated as soon as CDI has been confirmed or when there is a strong clinical suspicion of disease. If possible, antibiotics used for other infections should be stopped.1,3 Appropriate regimens for CDI depend on disease severity and presentation. Table 2 describes the various treatment recommendations. The current recommendation for second disease recurrence is a vancomycin taper regimen, but recent evidence suggests that this does not provide long-term benefit over a nontaper regimen,26 and growing evidence of the benefit of FMT is leading to its becoming an emerging treatment of choice.27 FMT has not been studied in the LTCF population. Antiperistaltic agents such as loperamide worsen the outcomes in CDI and are not recommended for control of symptoms.3,16,28

Conclusion

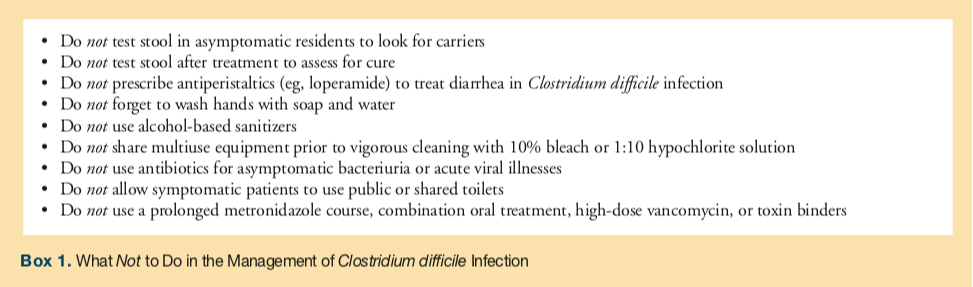

CDI is not well-studied in LTCFs, but providers can reduce the rates of transmission by educating residents and staff on proper hand hygiene techniques. Appropriate room-cleaning protocols for thorough disinfection of C diff organisms and spores also play a key role in prevention and reducing transmission. Box 1 provides an overview of what not to do in the management of CDI.

The following Tip Sheet can be disseminated to LTCF staff for educational purposes and quick reference.

References

1. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498.

2. Marshall LL, Peasah S, Stevens GA. Clostridium difficile infection in older adults: systematic review of efforts to reduce occurrence and improve outcomes. Consult Pharm. 2017;32(1):24-41.

3. Fletcher KR, Cinalli M. Identification, optimal management, and infection control measures for Clostridium difficile–associated disease in long-term care. Geriatr Nurs. 2007;28(3):171-181.

4. Chopra T, Goldstein EJC. Clostridium difficile infection in long-term care facilities: a call to action for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(suppl 2):S72-S76.

5. Rodriguez C, Taminiau B, Korsak N, et al. Longitudinal survey of Clostridium difficile presence and gut microbiota composition in a Belgian nursing home. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):229.

6. Zarowitz BJ, Allen C, O’Shea T, Strauss ME. Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and treatment differences between residents with and without nursing home- and non-nursing home-acquired Clostridium difficile infection. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(7):585-595.

7. Laffan AM, Bellantoni MF, Greenough WB III, Zenilman JM. Burden of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1068-1073.

8. Ziakas PD, Joyce N, Zacharioudakis IM, et al. Prevalence and impact of Clostridium difficile infection in elderly residents of long-term care facilities, 2011: a nationwide study. Medicine. 2016;95(31):e4187.

9. Yu H, Baser O, Wang L. Burden of Clostridium difficile-associated disease among patients residing in nursing homes: a population-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):193.

10. Mylotte JM, Russell S, Sackett B, Vallone M, Antalek M. Surveillance for Clostridium difficile infection in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):122-125.

11. Kim JH, Toy D, Muder RR. Clostridium difficile infection in a long-term care facility: hospital-associated illness compared with long-term care–associated illness. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(7):656-660.

12. Ponnada S, Guerrero DM, Jury LA, et al. Acquisition of Clostridium difficile colonization and infection after transfer from a Veterans Affairs hospital to an affiliated long-term care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(9):1070-1076.

13. Aldeyab MA, Cliffe S, Scott M, et al. Risk factors associated with Clostridium difficile infection severity in hospitalized patients. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(6):689-690.

14. Karanika S, Grigoras C, Flokas ME, et al. The attributable burden of Clostridium difficile infection to long-term care facilities stay: a clinical study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1733-1740.

15. Simor AE, Bradley SF, Strausbaugh LJ, Crossley K, Nicolle LE; SHEA Long-Term–Care Committee. Clostridium difficile in long-term–care facilities for the elderly. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(11):696-703.

16. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

17. Spinler JK, Ross CL, Savidge TC. Probiotics as adjunctive therapy for preventing Clostridium difficile infection—What are we waiting for? Anaerobe. 2016;41:51-57.

18. Messinger-Rapport BJ, Cruz-Oliver DM, Thomas DR, Morley JE. Clinical update on nursing home medicine: 2012. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):581-594.

19. Lau CSM, Chamberlain RS. Probiotics are effective at preventing Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:27-37.

20. Larson E, Bobo L, Bennett R, et al. Lack of care giver hand contamination with endemic bacterial pathogens in a nursing home. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20(1):11-15.

21. Brooks SE, Veal RO, Kramer M, Dore L, Schupf N, Adachi M. Reduction in the incidence of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in an acute care hospital and a skilled nursing facility following replacement of electronic thermometers with single-use disposables. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(2):98-103.

22. Chapman BC, Moore HB, Overbey DM, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant in patients with Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(4):756-764.

23. Polage CR, Gyorke CE, Kennedy MA, et al. Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1792-1801.

24. Dubberke ER, Burnham CA-D. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection: treat the patient, not the test. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1801-1802.

25. Roghmann M-C, Andronescu LR, Stucke EM, Johnson JK. Clostridium difficile colonization of nursing home residents. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(10):1267-1268.

26. Gentry CA, Giancola SE, Thind S, Kurdgelashvili G, Skrepnek GH, Williams RJ II. A propensity-matched analysis between standard versus tapered oral vancomycin courses for the management of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(4):ofx235.

27. Rao K, Safdar N. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):56-61.

28. Kato H, Kato H, Iwashima Y, Nakamura M, Nakamura A, Ueda R. Inappropriate use of loperamide worsens Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(2):194-195.

29. Rodriguez C, Korsak N, Taminiau B, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in elderly nursing home residents. Anaerobe. 2014;30:184-187.

30. Al-Tureihi FIJ, Hassoun A, Wolf-Klein G, Isenberg H. Albumin, length of stay, and proton pump inhibitors: key factors in Clostridium difficile-associated disease in nursing home patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(2):105-108.

31. Soriano MM, Johnson S. Treatment of Clostridium difficile infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(1):93-108.